Staff Ride Handbook for

the Battle of Shiloh,

6-7 April 1862

LTC Jeffrey J. Gudmens

and the Staff Ride Team

Combat Studies Institute

Combat Studies Institute Press

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027

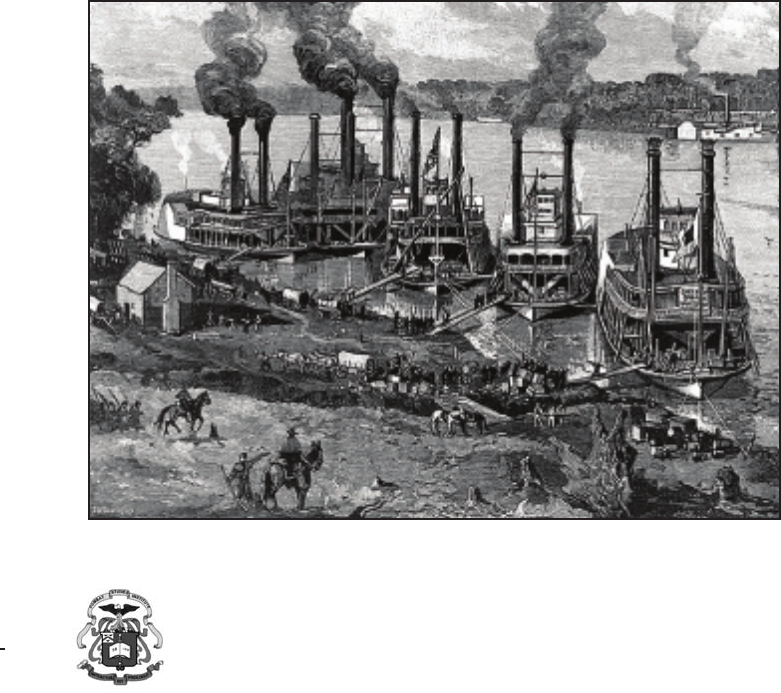

Cover photo: “Pittsburg Landing After the Battle of Shiloh,” #68448, Naval

Historical Center, Washington Navy Yard, DC.

Staff Ride Handbook for

the Battle of Shiloh,

6-7 April 1862

LTC Jeffrey J. Gudmens

and the Staff Ride Team

Combat Studies Institute

Combat Studies Institute Press

Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 66027

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Gudmens, Jeffrey J., 1960-

Staff ride handbook for the Battle of Shiloh, 6-7 April 1862 / Jeffrey J.

Gudmens and the Staff Ride Team, Combat Studies Institute.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

1. Shiloh, Battle of, Tenn., 1862. 2. Shiloh National Military Park

(Tenn.)—Guidebooks. 3. Staff rides—Tennessee—Shiloh National Mili-

tary Park. I. U.S.Army Command and General Staff College. Combat

Studies Institute. Staff Ride Team. II. Title.

E473.54.G84 2005

973.7’31—dc22

2004026445

i

Contents

Page

Illustrations .. ...........................................................................................iii

Foreword ................................................................................................. v

Introduction ...................................................................................vii

I. Civil War Armies

.........................................................................1

Organization ...................................................................................... 1

The US Army in 1861 ................................................................. 1

Raising the Armies ...................................................................... 2

The Leaders ................................................................................. 6

Civil War Staffs ........................................................................... 7

The Armies at Shiloh................................................................... 8

Weapons .......................................................................................... 10

Infantry ..................................................................................... 10

Cavalry ...................................................................................... 13

Field Artillery ............................................................................ 14

Heavy Artillery—Siege and Seacoast ....................................... 15

Weapons at Shiloh ..................................................................... 16

Tactics ........................................................................................... 18

Tactical Doctrine in 1861 .......................................................... 18

Early War Tactics ...................................................................... 20

Later War Tactics....................................................................... 22

Summary ................................................................................... 24

Tactics at Shiloh ........................................................................ 25

Logistics Support............................................................................. 27

Logistics at Shiloh..................................................................... 31

Engineer Support............................................................................. 32

Engineers at Shiloh ................................................................... 34

Communications Support ................................................................ 34

Communications at Shiloh ........................................................ 36

Medical Support .............................................................................. 38

Medical Support at the Battle of Shiloh .................................... 39

II. Shiloh Campaign Overview ............................................................ 43

III. Suggested Routes and Vignettes...................................................... 59

Introduction ..................................................................................... 59

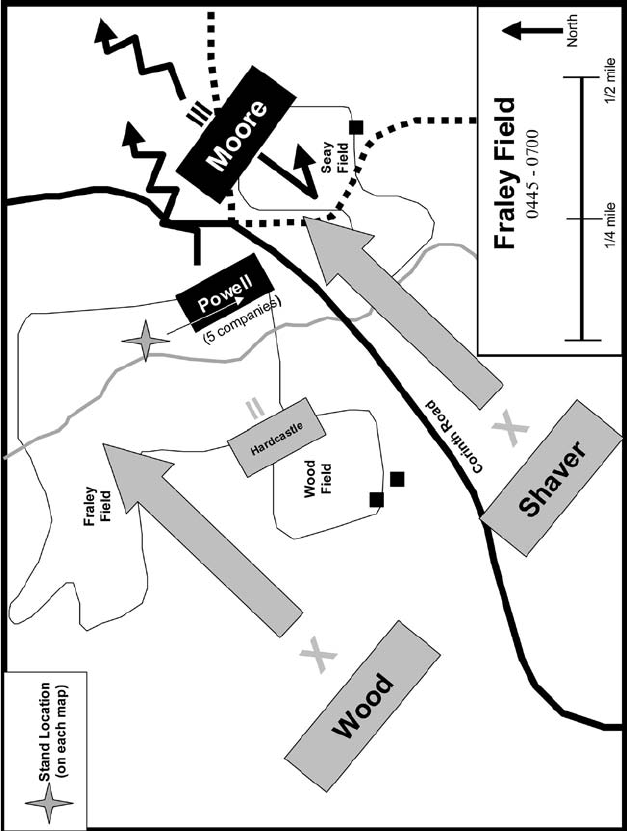

Stand 1, Fraley Field ....................................................................... 61

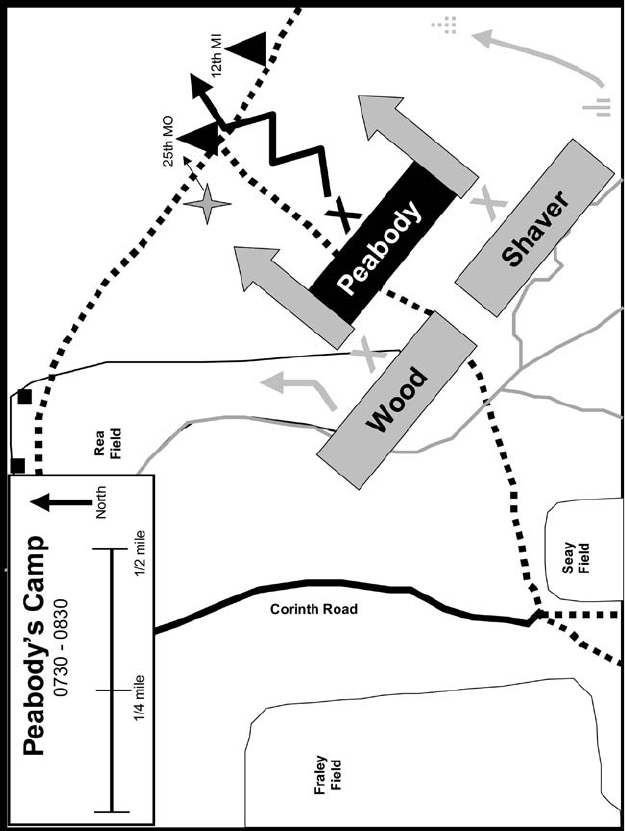

Stand 2, Peabody’s Camps .............................................................. 64

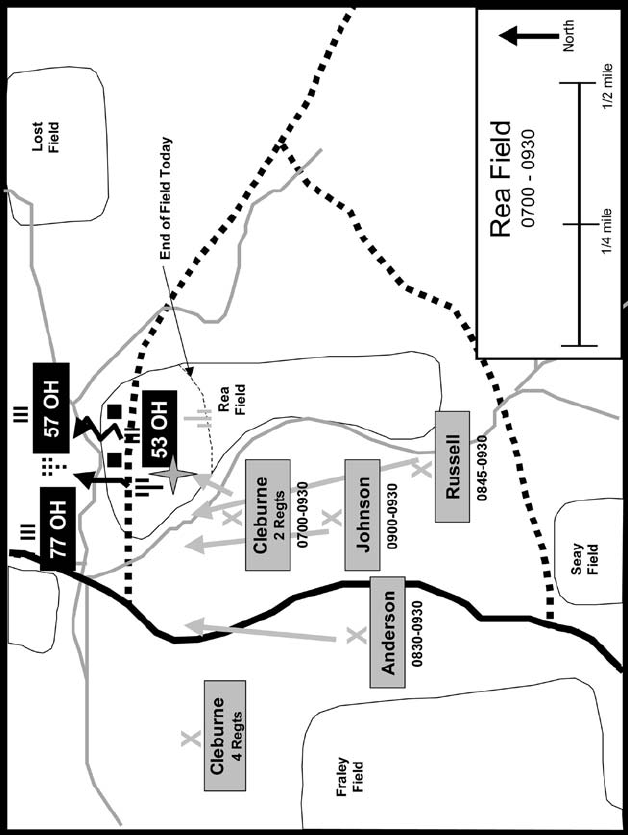

Stand 3, Rea Field ........................................................................... 67

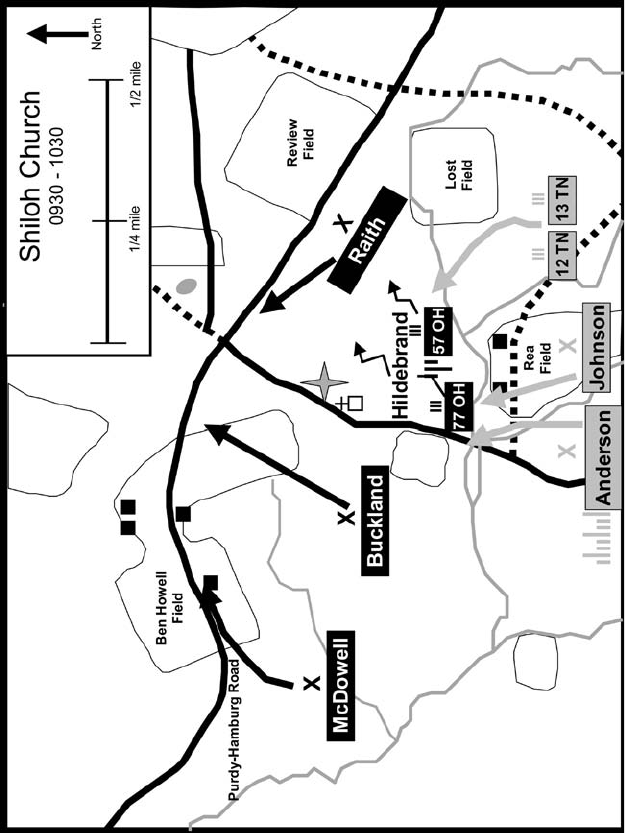

Stand 4, Shiloh Church.................................................................... 71

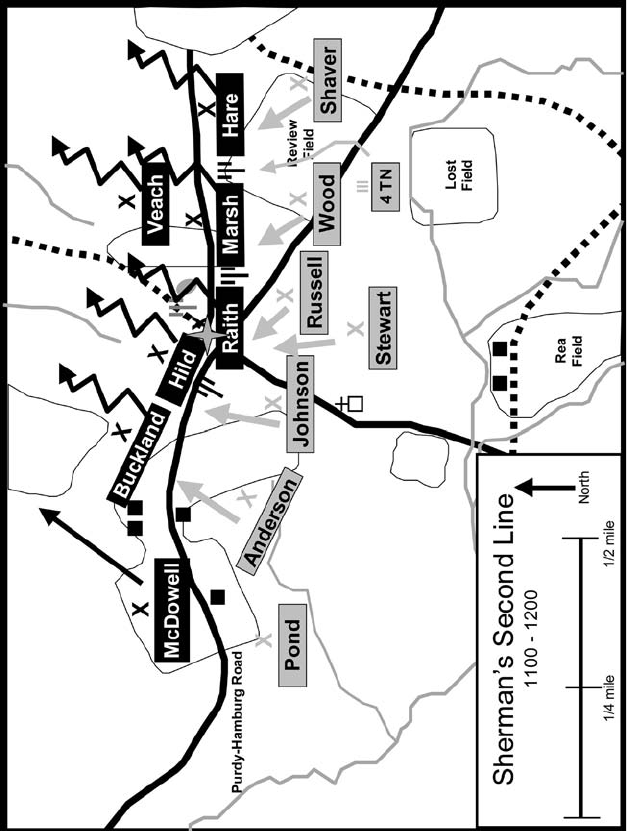

Stand 5, Sherman’s Second Line..................................................... 75

ii

iii

Page

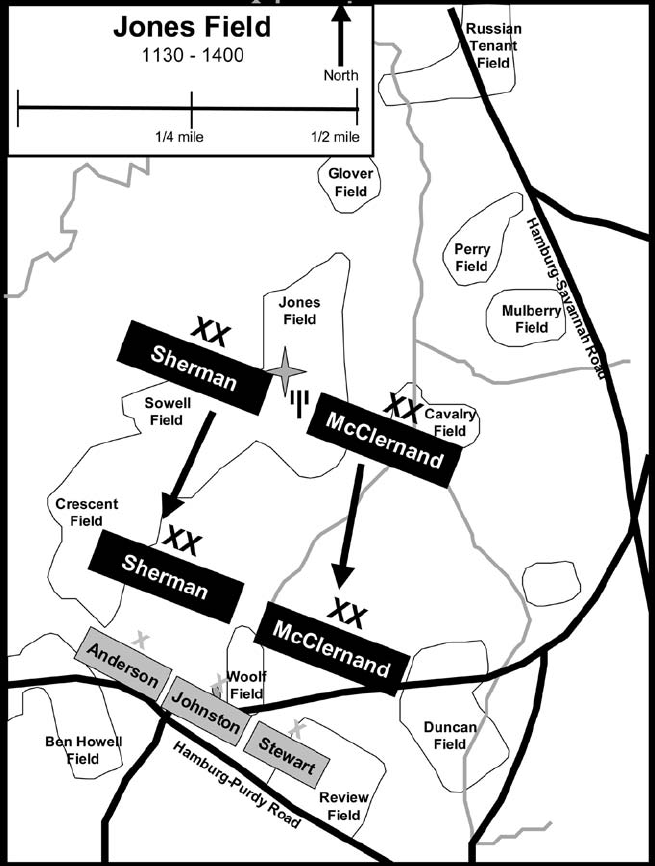

Stand 6, Jones Field......................................................................... 80

Stand 7, Lew Wallace’s Division .................................................... 83

Stand 8, Spain Field ........................................................................ 87

Stand 9, Stuart’s Brigade................................................................. 91

Stand 10, The Peach Orchard.......................................................... 96

Stand 11, Johnston’s Death ............................................................. 99

Stand 12, The Hornet’s Nest ......................................................... 103

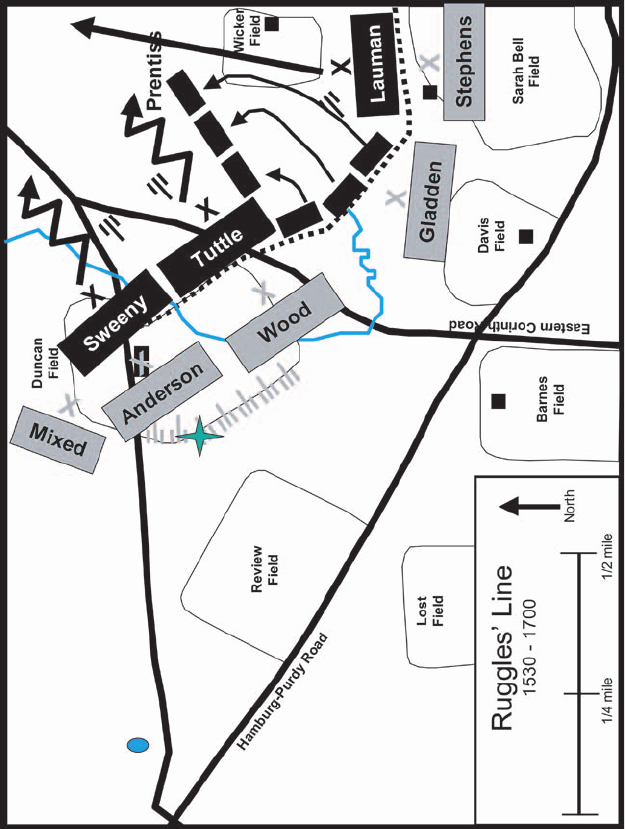

Stand 13, Ruggles’ Line ................................................................ 107

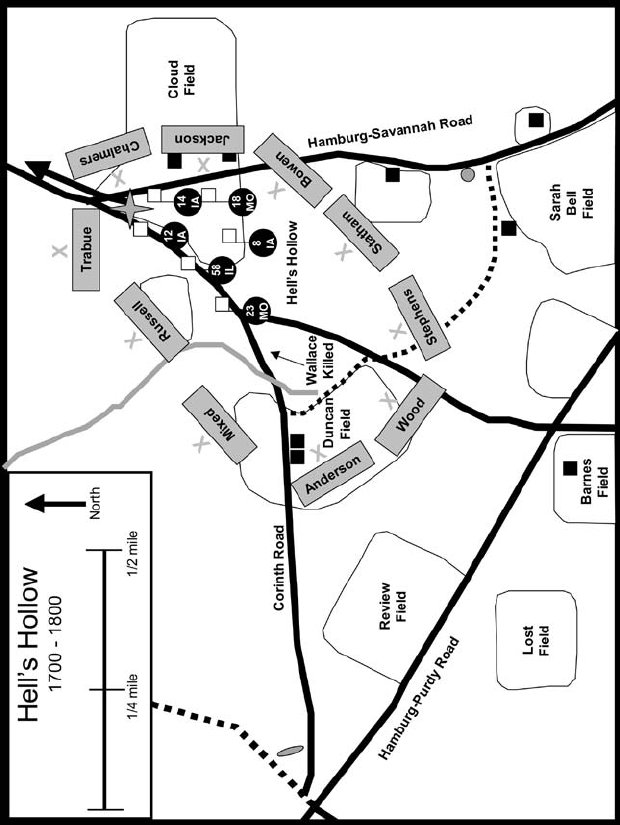

Stand 14, Hell’s Hollow ................................................................ 110

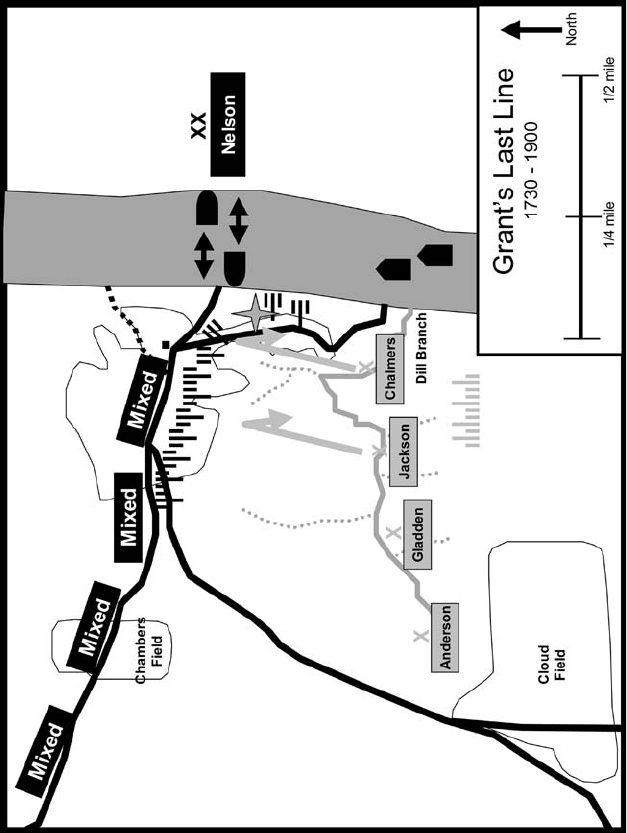

Stand 15, Grant’s Last Line .......................................................... 113

Stand 16, The Night ...................................................................... 116

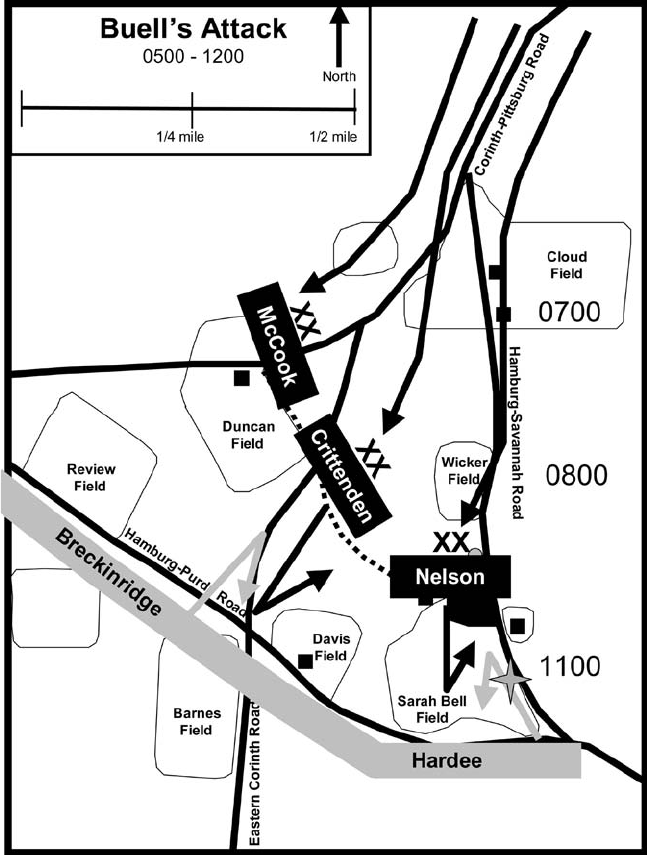

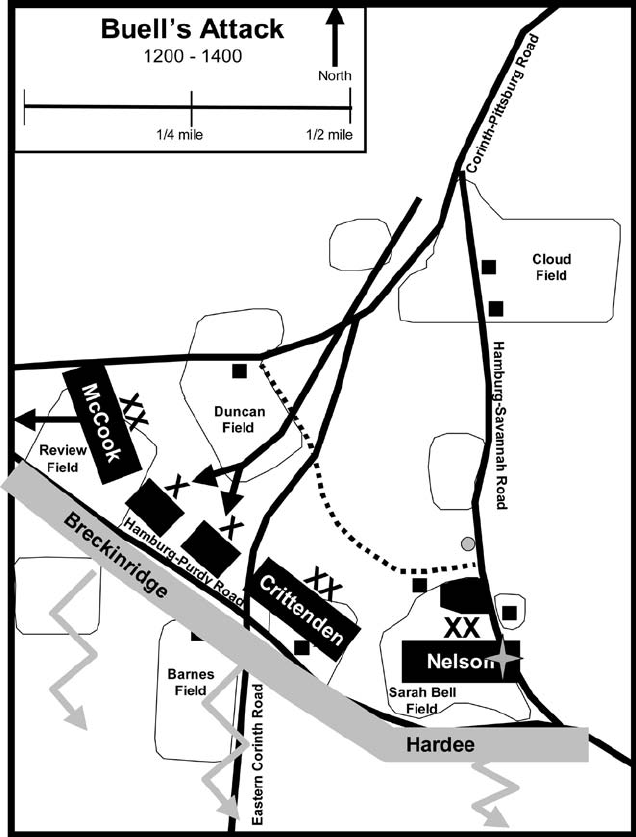

Stand 17, Buell’s Attack................................................................ 121

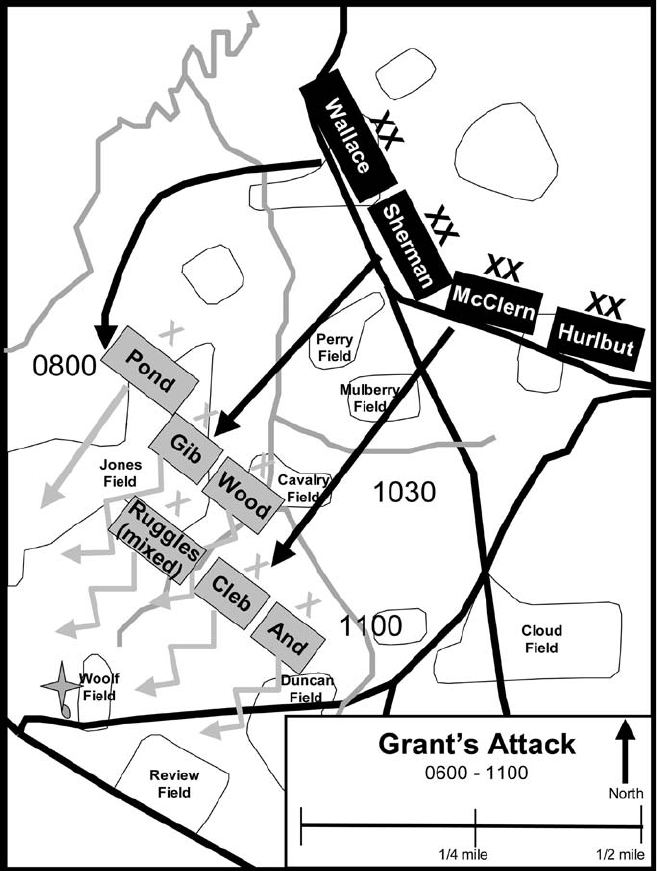

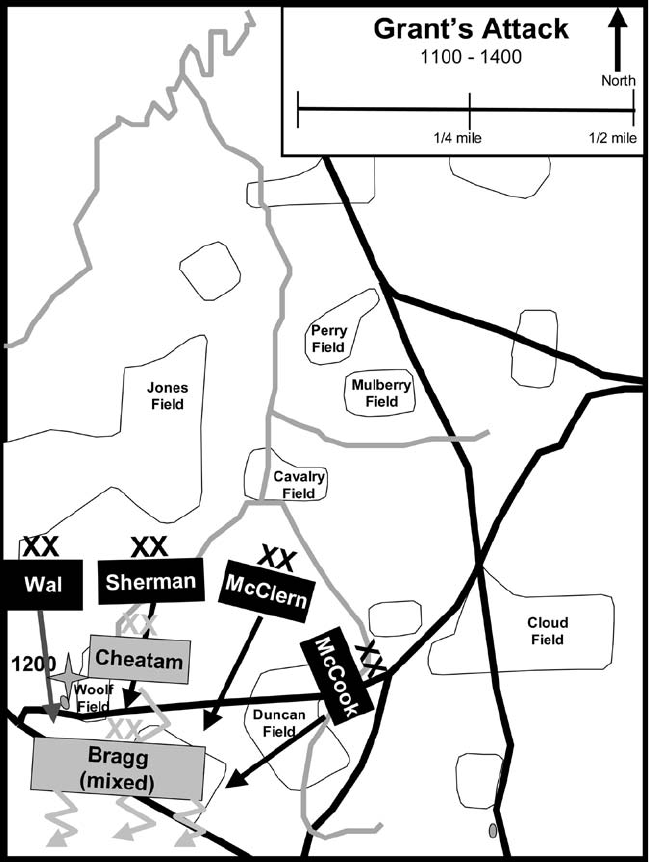

Stand 18, Grant’s Attack ............................................................... 126

Stand 19, The Cost ........................................................................ 129

Stand 20, The War is Won............................................................. 131

IV. Integration Phase for the Battle of Shiloh ..................................... 133

V. Support for a Staff Ride to Shiloh ................................................. 135

Appendix A. Order of Battle, Union Forces ....................................... 137

Appendix B. Order of Battle, Confederate Forces.............................. 141

Appendix C. Biographical Sketches ................................................... 143

Appendix D. Medal of Honor Conferrals for the Battle of Shiloh ..... 151

Bibliography ........................................................................................ 153

About the Author.................................................................................. 159

ii

iii

Illustrations

Tables

Page

1. Federal and Confederate Organized Forces ........................................ 6

2. Typical Staffs ......................................................................................7

3. Common Types of Artillery Available at the Battle of Shiloh .......... 17

4. Sample of Federal Logistics Data ..................................................... 30

Maps

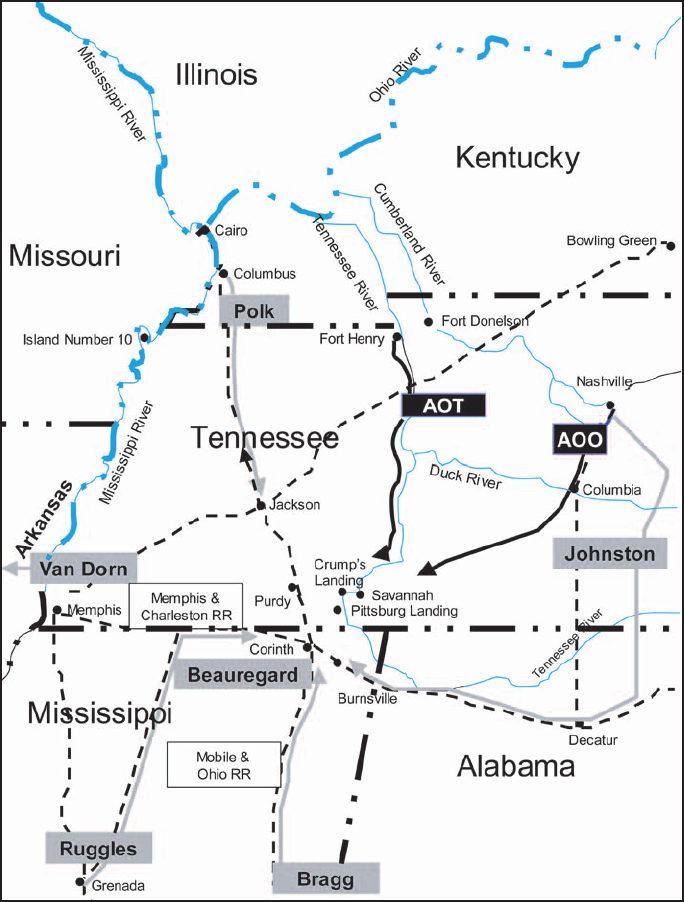

1. Operational Movement .....................................................................42

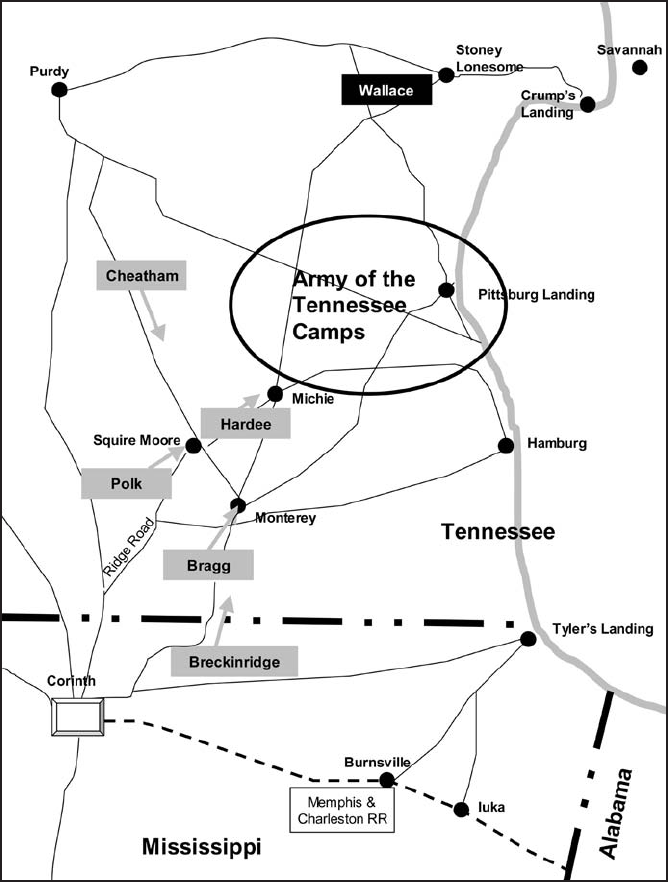

2. Army of the Tennessee Camps..........................................................52

3. The Confederate Plan........................................................................54

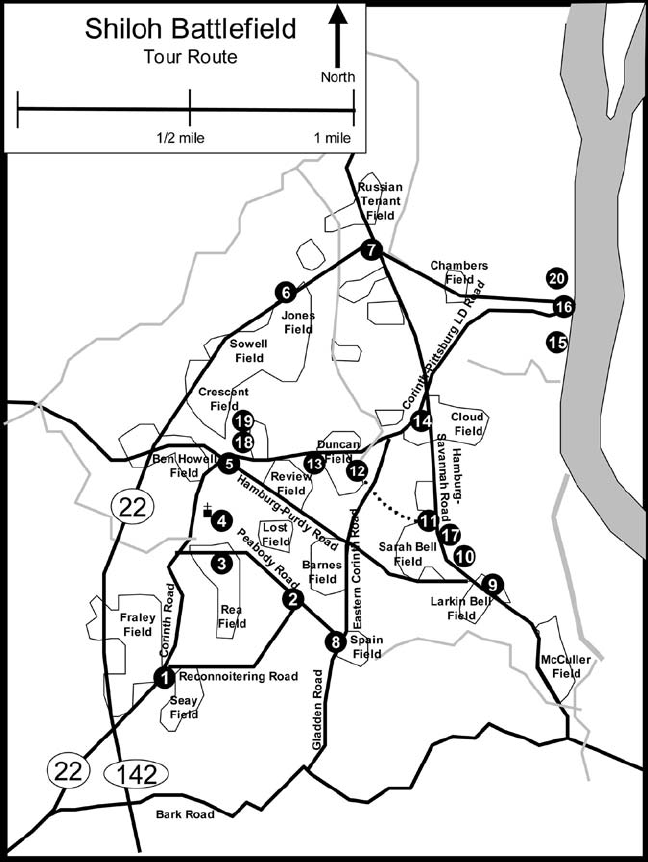

4. Shiloh Battleeld, Tour Route...........................................................56

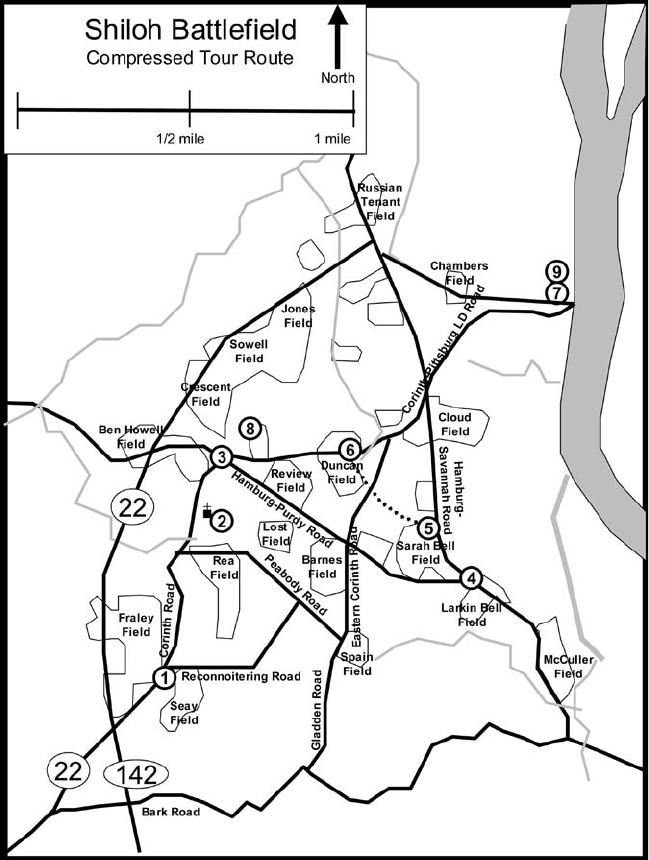

5. Shiloh Battleeld, Compressed Tour Route......................................57

6. Fraley Field .......................................................................................60

7. Peabody’s Camp................................................................................63

8. Rea Field ...........................................................................................66

9. Shiloh Church ...................................................................................70

10. Sherman’s Second Line.....................................................................74

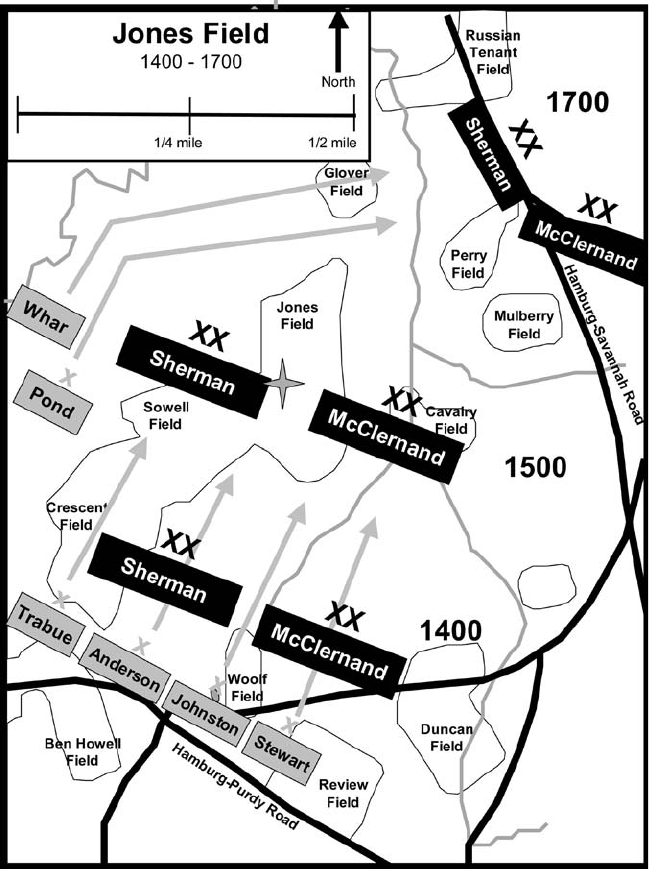

11. Jones Field, 1130-1400 .....................................................................78

12. Jones Field, 1400-1700 .....................................................................79

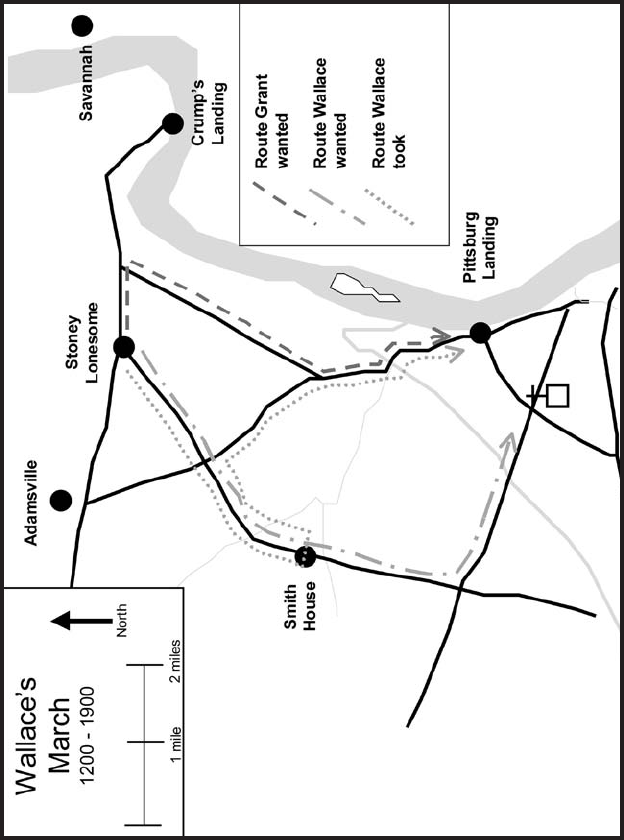

13. Wallace’s March................................................................................82

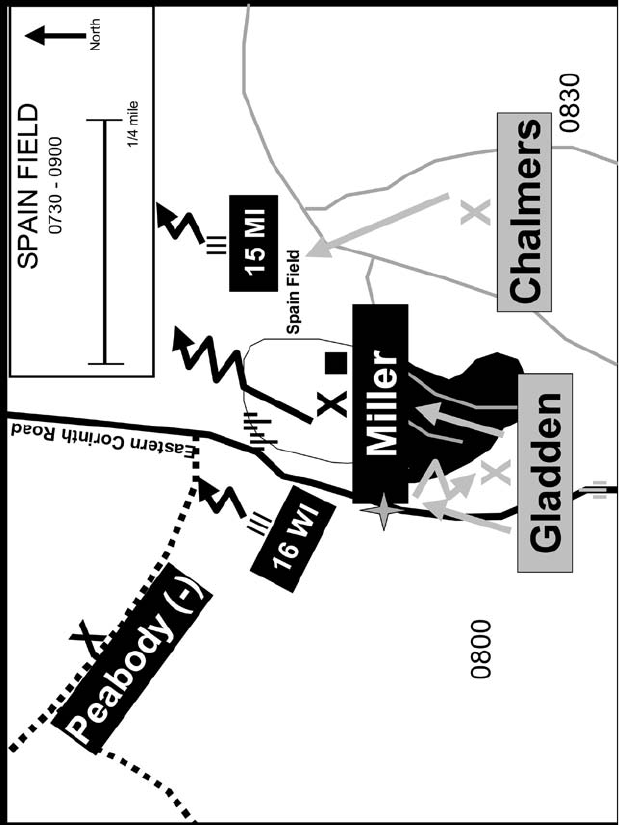

14. Spain Field ........................................................................................86

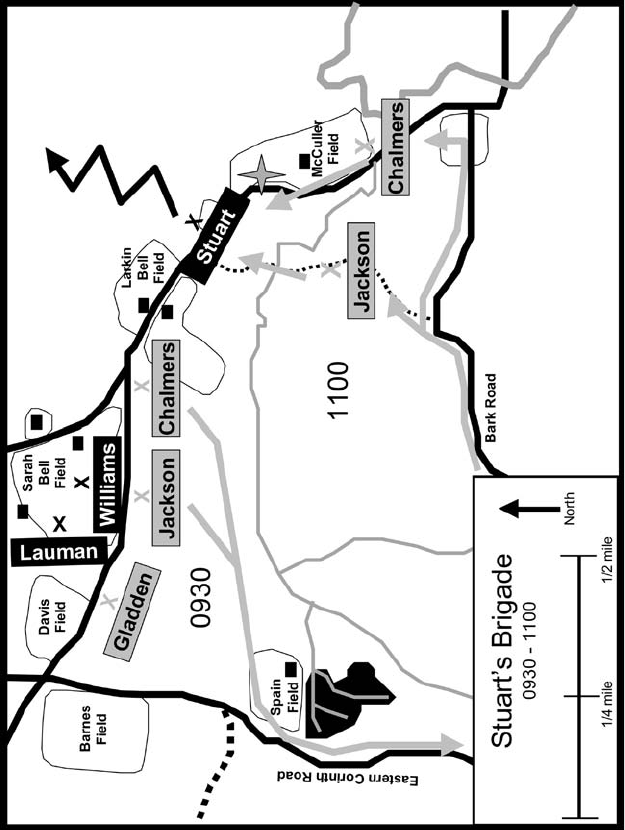

15. Stuart’s Brigade.................................................................................90

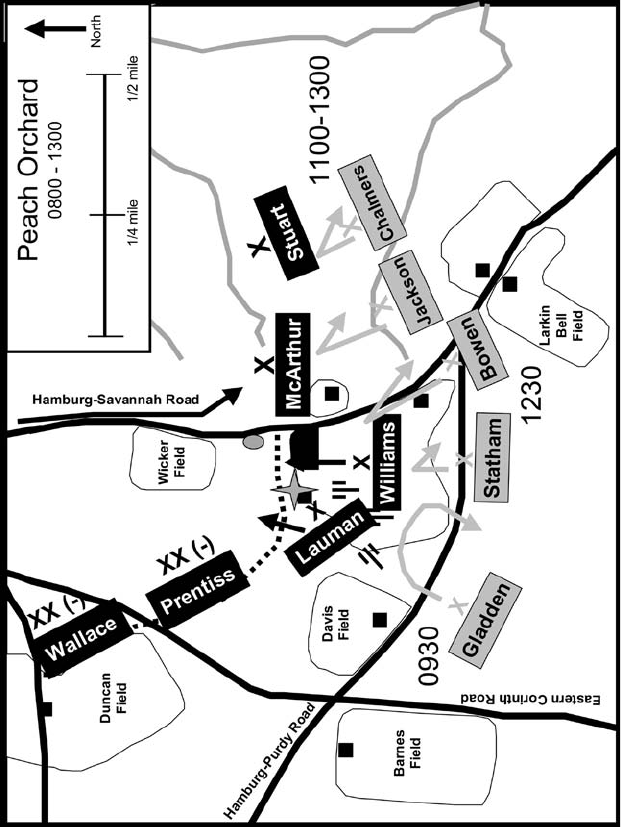

16. Peach Orchard, 0800-1300................................................................94

17. Peach Orchard, 1300-1600................................................................95

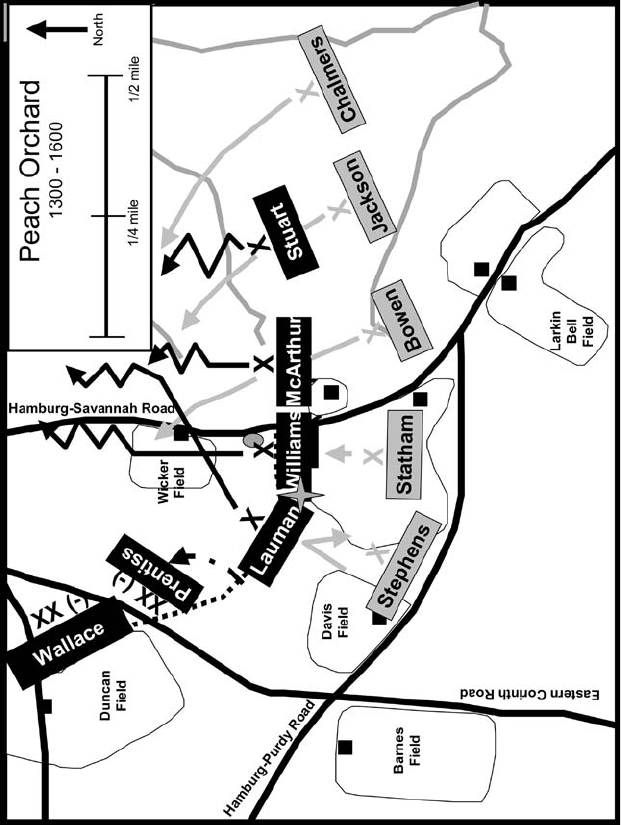

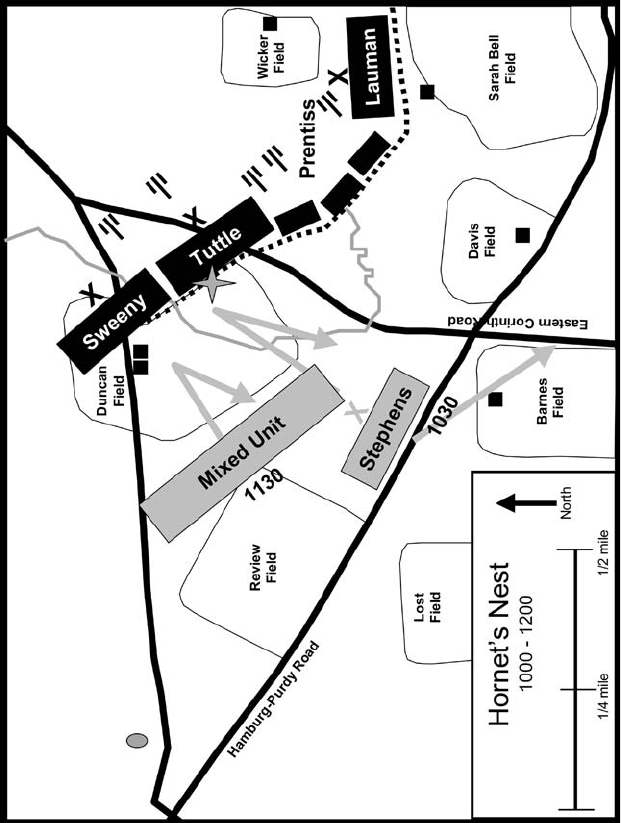

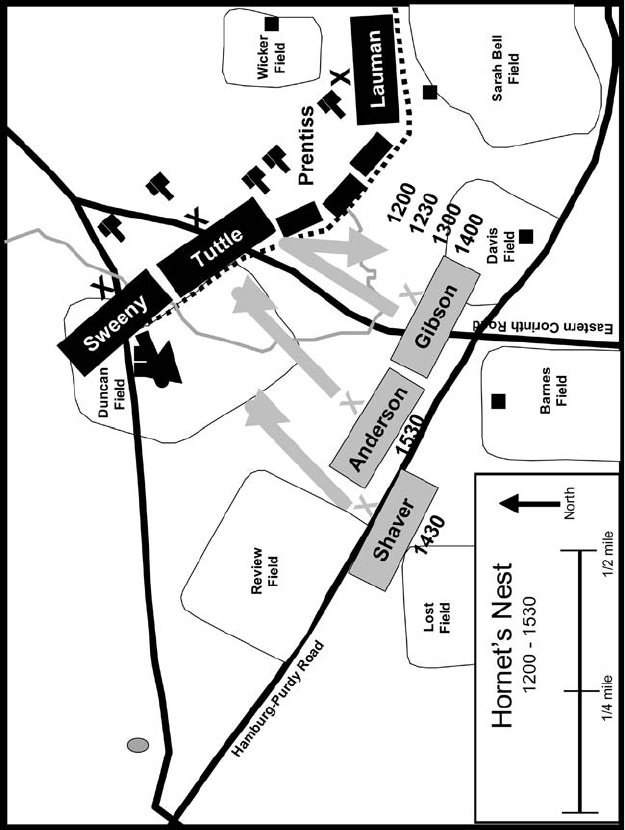

18. Hornet’s Nest, 1000-1200 ...............................................................101

19. Hornet’s Nest, 1200-1530 ...............................................................102

20. Ruggles’ Line ..................................................................................106

21. Hell’s Hollow ..................................................................................109

22. Grant’s Last Line.............................................................................112

23. The Night ........................................................................................115

24. Buell’s Attack, 0500-1200...............................................................119

25. Buell’s Attack, 1200-1400...............................................................120

26. Grant’s Attack, 0600-1100 ..............................................................124

27.

Grant’s Attack, 1100-1400 ..............................................................125

v

v

Foreword

Since the early 20th century the US Army has used Civil War and oth-

er battleelds as “outdoor classrooms” in which to educate and train its of-

cers. Employing a methodology developed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas,

in 1906, both the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College and US

Army War College conducted numerous battleeld staff rides to prepare

ofcers for duties in both war and peace. Often interrupted by the exigen-

cies of the nation’s wars, the tradition was renewed and reinvigorated at

Fort Leavenworth in the early 1980s. Since 1983 the Leavenworth Staff

Ride Team has guided military students on battleelds around the world.

For those unable to avail themselves directly of the team’s services the

Combat Studies Institute has begun to produce a series of staff ride guides

to serve in lieu of a Fort Leavenworth instructor. The newest volume in

that series, Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Gudmens’ Staff Ride Handbook for

the Battle of Shiloh, 6-7 April 1862 is a valuable study that examines the

key considerations in planning and executing the campaign and battle.

Modern tacticians and operational planners will nd themes that still reso-

nate. Gudmens demonstrates that leaders in Blue and Gray, in facing the

daunting tasks of this, the bloodiest battle to this point on the continent,

rose to the challenge. They were able to meet this challenge through plan-

ning, discipline, ingenuity, leadership, and persistence—themes worthy of

reection by today’s leaders.

Thomas T. Smith

Lieutenant Colonel, Infantry

Director of Combat Studies

vii

vii

Introduction

A staff ride to a major battleeld is an excellent tool for the historical

education of members of the Armed Forces. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas,

has been conducting staff rides since the 1900s. Captain Arthur L. Wagner

was an instructor at Fort Leavenworth in the 1890s, and he believed an

ofcer’s education had become too far removed from the reality of war.

He pondered how to get the experience of combat to ofcers who had only

experienced peace. His answer was the staff ride, a program in which stu-

dents studied a major battle and then went to the actual eld to complete

the study. Wagner did not live to see staff rides added to the curriculum

at Fort Leavenworth, but in 1906, the rst staff ride was added to the Fort

Leavenworth “experience.” Major Eben Swift led 12 students on a study

of the Atlanta Campaign of 1864. On and off, staff rides have been a part

of the curriculum ever since.

Staff rides are not just limited to schoolhouse education. For years,

unit commanders have conducted numerous staff rides to varied battle-

elds as part of their ofcers’ and soldiers’ professional development. In

support of these eld commanders, the Combat Studies Institute at Fort

Leavenworth published staff ride guides to assist personnel planning and

conducting staff rides worldwide.

In 2002, General John Abrams, US Army Training and Doctrine

Command (TRADOC) commanding general, recognized the impact and

importance of staff rides and revamped the Staff Ride Team. TRADOC

assigned personnel full time to Fort Leavenworth to lead staff rides for the

Army. As part of this initiative, the Staff Ride Team is also dedicated to

publishing staff ride handbooks in support of the Army.

The Staff Ride Handbook for the Battle of Shiloh, 6-7 April 1862 pro-

vides a systematic approach to the analysis of this early battle in the west-

ern theater of the American Civil War. Part I describes the organization of

both armies, detailing their weapons, tactics, logistics, engineering, com-

munications, and medical support. Part II consists of a campaign overview

that allows students to understand how the armies met on the battleeld.

Part III is a suggested route for conducting a staff ride at Shiloh. For each

stop, or “stand,” there is a set of travel directions, a description of the ac-

tion that occurred there, vignettes by battle participants, a list of discussion

or teaching points that a staff ride leader can explore at the stand, and a

map of the battle actions.

Part IV provides information on conducting the integration phase of

a staff ride. Suggested areas of discussion for use during the integration

viii

phase are included. Part V provides information on conducting a staff ride

at Shiloh, including sources of assistance and logistics considerations. Ap-

pendix A provides the order of battle, including numbers engaged and ca-

sualties. Appendix B provides key participants’ biographical information.

Appendix C is a list of Medal of Honor recipients for actions at Shiloh. An

annotated bibliography gives sources for preliminary study.

1

I. Civil War Armies

Organization

The US Army in 1861

On the eve of the Civil War the Regular Army of the United States

was essentially a frontier constabulary whose 16,000 ofcers and men

were organized into 198 companies scattered across the nation at 79 dif-

ferent posts. At the start of the war, 183 of these companies were either

on frontier duty or in transit while the remaining 15, mostly coastal artil-

lery batteries, guarded the Canadian border and Atlantic coast or one of

23 arsenals. In 1861, this Army was under the command of Lieutenant

General Wineld Scott, the 75-year-old hero of the Mexican-American

War. His position as general in chief was traditional, not statutory, because

Secretaries of War since 1821 had designated a general to be in charge of

the eld forces without formal congressional approval. The eld forces

were controlled through a series of geographic departments whose com-

manders reported directly to the general in chief. Both sides would use

this frequently modied department system throughout the Civil War for

administering regions under Army control.

Army administration was handled by a system of bureaus whose

senior ofcers were, by 1860, in the twilight of long careers in their

technical elds. Six of the 10 bureau chiefs were more than 70 years old.

Modeled after the British system, these bureaus answered directly to the

War Department and were not subject to the general in chief’s orders.

Predecessors of many of today’s combat support and combat service sup-

port branches, the following bureaus had been established by 1861:

Quartermaster Medical

Ordnance Adjutant General

Subsistence Paymaster

Engineer Inspector General

Topographic Engineer* Judge Advocate General

*Merged with the Engineer Bureau in 1863.

During the war Congress elevated the Ofce of the Provost Marshal and

the Signal Corps to bureau status and created a Cavalry Bureau. Note that

no operational planning or intelligence staff existed. American command-

ers before the Civil War had never required such a structure.

This system provided suitable civilian control and administrative

support to the small field army before 1861. Ultimately the bureau

2

3

system would respond effectively, if not always efciently, to the mass

mobilization required over the next four years. Indeed, it would remain es-

sentially intact until the early 20th century. The Confederate government,

forced to create an army and support organization from scratch, estab-

lished a parallel structure to that of the US Army. In fact, many important

gures in Confederate bureaus had served in one of the prewar bureaus.

Raising the Armies

With the outbreak of war in April 1861, both sides faced the monu-

mental task of organizing and equipping armies that far exceeded the pre-

war structure in size and complexity. The Federals maintained control of

the Regular Army, and the Confederates initially created a Regular force,

mostly on paper. Almost immediately the North lost many of its ofcers to

the South, including some of exceptional quality. Of 1,108 Regular Army

ofcers serving as of 1 January 1861, 270 ultimately resigned to join the

South. Only a few hundred of the 15,135 enlisted men, however, left the

ranks because the private soldiers did not have the option of resigning.

The federal government had two basic options for using the Regular

Army. It could be divided into training and leadership cadre for newly

formed volunteer regiments or be retained in units to provide a reliable

nucleus for the Federal Army in coming battles. At the start, Scott envi-

sioned a relatively small force to defeat the rebellion and therefore insisted

that the Regulars ght as units. Although some Regular units fought well

at the First Battle of Bull Run and in other battles, Scott’s decision ulti-

mately limited Regular units’ impact on the war. Battle losses and disease

soon thinned the ranks of Regulars, and ofcials could never recruit suf-

cient replacements in the face of stiff competition from the states that were

forming volunteer regiments. By November 1864, many Regular units had

been so depleted that they were withdrawn from front-line service. The

war, therefore, was fought primarily with volunteer ofcers and men, the

vast majority of whom had no previous military training or experience.

Neither side had difculty in recruiting the numbers initially required

to ll the expanding ranks. In April 1861, President Abraham Lincoln

called up 75,000 men from the states’ militias for three months. This

gure probably represented Lincoln’s informed guess as to how many

troops would be needed to quell the rebellion quickly. Almost 92,000 men

responded because most Northern states recruited their “organized” but

untrained militia companies. At the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861,

these ill-trained, poorly equipped soldiers generally fought much better

than they were led. Later, as the war began to require more manpower,

2

3

the federal government set enlisted quotas through various “calls,” which

local districts struggled to ll. Similarly, the Confederate Congress autho-

rized the acceptance of 100,000 one-year volunteers in March 1861. One-

third of these men were under arms within a month. The southern spirit

of voluntarism was so strong that possibly twice that number could have

been enlisted, but sufcient arms and equipment were not then available.

As the war continued and casualty lists grew, the glory of volunteer-

ing faded, and both sides ultimately resorted to conscription to help ll the

ranks. The Confederates enacted the rst conscription law in American

history in April 1862, followed by the federal government’s own law in

March 1863. Throughout these rst experiments in American conscription,

both sides administered the programs in less than a fair and efcient way.

Conscription laws tended to exempt wealthier citizens, and initially, draft-

ees could hire substitutes or pay commutation fees. As a result, the average

conscript’s health, capability, and morale were poor. Many eligible men,

particularly in the South, enlisted to avoid the onus of being considered a

conscript. Still, conscription or the threat of conscription ultimately helped

provide a sufcient quantity of soldiers for both sides.

Conscription was never a popular program, and the North, in particu-

lar, tried several approaches to limit conscription requirements. These ef-

forts included offering lucrative bounties, or fees paid to induce volunteers

to ll required quotas. In addition, the Federals offered a series of reenlist-

ment bonuses—money, 30-day furloughs, and an opportunity for veteran

regiments to maintain their colors and be designated as “veteran” volun-

teer infantry regiments. The Federals also created an Invalid Corps (later

renamed the Veteran Reserve Corps) of men unt for front-line service

who performed essential rear area duties. The Union also recruited almost

179,000 blacks, mostly in federally organized volunteer regiments. By

February 1864, blacks were being conscripted in the North. In the South,

recruiting or conscripting slaves was so politically sensitive that it was not

attempted until March 1865, far too late to inuence the war.

Whatever the faults of the manpower mobilization, it was an impres-

sive achievement, particularly as a rst effort on such a scale. Various

enlistment gures exist, but the best estimates are that approximately 2

million men served in the Federal Army during 1861-1865. Of that num-

ber, 1 million were under arms at the end of the war. Because Confederate

records are incomplete or were lost, estimates of their enlistments vary

from 600,000 to more than 1.5 million. Most likely, between 750,000

and 800,000 men served in the Confederacy during the war, with a peak

strength never exceeding 460,000. Perhaps the greatest legacy of the

4

5

manpower mobilization efforts of both sides was the improved Selective

Service System that created the American armies of World War I and

World War II.

The unit structure into which the expanding armies were organized was

generally the same for Federals and Confederates, reecting the common

roots for both armies. The Federals began the war with a Regular Army or-

ganized into an essentially Napoleonic, musket-equipped structure. Each

of the 10 prewar infantry regiments consisted of 10 87-man companies

with a maximum authorized strength of 878. At the beginning of the war,

the Federals added nine Regular infantry regiments with a newer “French

model” organizational structure. The new regiments contained three bat-

talions, with a maximum authorized strength of 2,452. The new Regular

battalion, with eight 100-man companies, was, in effect, equivalent to the

prewar regiment. Essentially an effort to reduce staff ofcer slots, the new

structure was unfamiliar to most leaders, and both sides used a variant

of the old structure for newly formed volunteer regiments. The Federal

War Department established a volunteer infantry regimental organization

with a strength that could range from 866 to 1,046, varying in authorized

strength by up to 180 infantry privates. The Confederate Congress xed

its 10-company infantry regiment at 1,045 men. Combat strength in battle,

however, was always much lower because of casualties, sickness, leaves,

details, desertions, and stragglers.

The battery remained the basic artillery unit, although battalion and

larger formal groupings of artillery emerged later in the war in the eastern

theater. Four understrength Regular regiments existed in the US Army

at the start of the war, and one Regular regiment was added in 1861,

for a total of 60 batteries. Nevertheless, most batteries were volunteer

organizations. A Federal battery usually consisted of six guns and had

an authorized strength of 80 to 156 men. A battery of six 12-pounder

Napoleons could include 130 horses. If organized as “horse” or ying

artillery, cannoneers were provided individual mounts, and more horses

than men could be assigned to the battery. Their Confederate counterparts,

plagued by limited ordnance and available manpower, usually operated

with a four-gun battery, often with guns of mixed types and calibers.

Confederate batteries seldom reached their initially authorized manning

level of 80 soldiers.

Prewar Federal mounted units were organized into ve Regular

regiments (two dragoon, two cavalry, and one mounted rie), and one

Regular cavalry regiment was added in May 1861. Originally, 10 com-

panies comprised a regiment, but congressional legislation in July 1862

4

5

ofcially reorganized the Regular mounted units into standard regiments

of 12 “companies or troops” of 79 to 95 men each. Although the term

“troop” was ofcially introduced, most cavalrymen continued to use the

more familiar term “company” to describe their units throughout the war.

The Federals grouped two companies or troops into squadrons, with four

to six squadrons making a regiment. Confederate cavalry units, organized

in the prewar model, authorized 10 76-man companies per regiment. Some

volunteer cavalry units on both sides also formed into smaller cavalry bat-

talions. Later in the war, both sides began to merge their cavalry regiments

and brigades into division and corps organizations.

For both sides, unit structure above regimental level was similar to

today’s structure, with a brigade controlling three to ve regiments and

a division controlling two or more brigades. Federal brigades generally

contained regiments from more than one state, while Confederate brigades

often had several regiments from the same state. In the Confederate Army,

a brigadier general usually commanded a brigade, and a major general

commanded a division. The Federal Army, with no rank higher than major

general until 1864, often had colonels commanding brigades and brigadier

generals commanding divisions.

The large numbers of organizations formed, as shown in table 1,

reect the politics of the time. The War Department in 1861 considered

making recruiting a federal responsibility, but this proposal seemed to be

an unnecessary expense for the short war initially envisioned. Therefore,

responsibility for recruiting remained with the states, and on both sides,

state governors continually encouraged local constituents to form new

volunteer regiments. This practice strengthened support for local, state,

and national politicians and provided an opportunity for glory and high

rank for ambitious men. Although such local recruiting created regiments

with strong bonds among the men, it hindered lling the ranks of existing

regiments with new replacements. As the war progressed, the Confederates

attempted to funnel replacements into units from their same state or

region, but the Federals continued to create new regiments. Existing

Federal regiments detailed men back home to recruit replacements, but

these efforts could never successfully compete for men joining new local

regiments. The newly formed regiments thus had no seasoned veterans to

train the recruits, and the battle-tested regiments lost men faster than they

could recruit replacements. Many regiments on both sides were reduced

to combat ineffectiveness as the war progressed. Seasoned regiments were

often disbanded or consolidated, usually against the wishes of the men

assigned.

6

7

Table 1. Federal and Confederate Organized Forces

Federal Confederate

Infantry 19 regular regiments 642 regiments

2,125 volunteer regiments 9 legions*

60 volunteer battalions 163 separate battalions

351 separate companies 62 separate companies

Artillery 5 regular regiments 16 regiments

61 volunteer regiments 25 battalions

17 volunteer battalions 227 batteries

408 separate batteries

Cavalry 6 regular regiments 137 regiments

266 volunteer regiments 1 legion*

45 battalions 143 separate battalions

78 separate companies 101 separate companies

*Legions were a form of combined arms team with artillery, cavalry, and infantry units.

They were approximately the strength of a large regiment. Long before the end of the war,

legions lost their combined arms organization.

The Leaders

Because the Confederate and Federal Armies’ organization, equipment,

tactics, and training were similar, units’ performance in battle often de-

pended on the quality and performance of their individual leaders. General

ofcers were appointed by their respective central governments. At the

start of the war, most, but certainly not all, of the more senior ofcers had

West Point or other military school experience. In 1861, Lincoln appointed

126 general ofcers, of which 82 were or had been professional ofcers.

Jefferson Davis appointed 89, of which 44 had received professional train-

ing. The remaining ofcers were political appointees, but of those only 16

Federal and seven Confederate generals had no military experience.

Of the volunteer ofcers who composed most of the leadership for

both armies, colonels (regimental commanders) were normally appointed

by state governors. Other eld grade ofcers were appointed by their

states, although many were initially elected within their units. The men

usually elected their company grade ofcers. This long-established militia

tradition, which seldom made military leadership and capability a primary

consideration, was largely an extension of the states’ rights philosophy and

sustained political patronage in both the Union and the Confederacy.

Much has been made of the West Point backgrounds of the men who

ultimately dominated the senior leadership positions of both armies, but

the graduates of military colleges were not prepared by such institutions

6

7

to command divisions, corps, or armies. Moreover, although many lead-

ers had some combat experience from the Mexican War era, very few had

experience above the company or battery level in the peacetime years

before 1861. As a result, the war was not initially conducted at any level

by “professional ofcers” in today’s terminology. Leaders became more

professional through experience and at the cost of thousands of lives.

General William T. Sherman would later note that the war did not enter its

“professional stage” until 1863.

Civil War Staffs

In the Civil War, as today, large military organizations’ success often

depended on the effectiveness of the commanders’ staffs. Modern staff

procedures have evolved only gradually with the increasing complexity

of military operations. This evolution was far from complete in 1861, and

throughout the war, commanders personally handled many vital staff func-

tions, most notably operations and intelligence. The nature of American

warfare up to the mid-19th century had not yet clearly overwhelmed single

commanders’ capabilities.

Civil War staffs were divided into a “general staff” and a “staff corps.”

This terminology, dened by Scott in 1855, differs from modern deni-

tions of the terms. Table 2 lists typical staff positions at army level, al-

though key functions are represented down to regimental level. Except for

the chief of staff and aides-de-camp, who were considered personal staff

and would often depart when a commander was reassigned, staffs mainly

Table 2. Typical Staffs

General Staff Chief of Staff

Aides

Assistant Adjutant General

Assistant Inspector General

Staff Corps Engineer

Ordnance

Quartermaster

Subsistence

Medical

Pay

Signal

Provost Marshal

Chief of Artillery

8

9

contained representatives of the various bureaus, with logistical areas be-

ing best represented. Later in the war, some truly effective staffs began to

emerge, but this was a result of the increased experience of the ofcers

serving in those positions rather than a comprehensive development of

standard staff procedures or guidelines.

George B. McClellan, when he appointed his father-in-law as his chief

of staff, was the rst American to use this title ofcially. Even though

many senior commanders had a chief of staff, the position was not used in

any uniform way and seldom did the man in this role achieve the central

coordinating authority of the chief of staff in modern headquarters. This

position, along with most other staff positions, was used as an individual

commander saw t, making staff responsibilities somewhat different

under each commander. This inadequate use of the chief of staff was

among the most important shortcomings of staffs during the Civil War.

An equally important weakness was the lack of any formal operations or

intelligence staff. Liaison procedures were also ill dened, and various

staff ofcers or soldiers performed this function with little formal guid-

ance. Miscommunication or lack of knowledge of friendly units proved

disastrous time after time.

The Armies at Shiloh

MG Henry Halleck assumed command of the newly created US De-

partment of the Mississippi on 11 March 1862. He was responsible for the

territory from the Mississippi River east to the Appalachian Mountains.

With headquarters in St. Louis, Halleck had three eld armies in his de-

partment: the Army of the Tennessee under the command of Major Gen-

eral (MG) Ulysses S. Grant, the Army of the Ohio under MG Don Carlos

Buell, and the Army of the Mississippi under MG John Pope. Only Grant

and Buell would see action at Shiloh; Pope would campaign against Island

No. 10.

Grant’s Army of the Tennessee was organized into six divisions with

a strength of 48,000 troops. The army was a mixed bag of veteran units

and “green” units. The experienced troops were veterans of the battles of

Fort Donelson and Fort Henry. MG John A. McClernand, a general who

had been a Democratic Congressman before the war, commanded the 1st

Division. By April 1862, McClernand was the ranking division command-

er in the Army of the Tennessee, and Grant had concerns about his abili-

ties and did not want him in command in his absence. The 1st Division

contained 7,000 Illinois and Iowa veteran troops in three brigades.

Brigadier General (BG) William Harvey Lamb Wallace commanded the

8

9

2d Division. Wallace had been a brigade commander under McClernand

at Fort Donelson and had only assumed command of the 2d Division on

22 March 1862 when MG Charles F. Smith was injured. The 2d Division

contained 8,500 veterans also from Illinois and Iowa in three brigades.

MG Lewis Wallace commanded the 3d Division. Wallace had fought

in the Mexican War and had seen action in western Virginia and at Fort

Donelson. The 3d Division contained 7,500 veterans in three brigades

from mainly Ohio and Indiana. BG Stephen A. Hurlbut commanded the

4th Division. Hurlbut was an Illinois politician known for hard drinking

and questionable business deals. The 4th Division, a mix of veterans and

inexperienced troops, contained 6,500 men in three brigades from Illinois,

Iowa, Indiana, and Kentucky. BG William T. Sherman commanded the 5th

Division. Sherman was the only West Point graduate division commander

in Grant’s army. Sherman had fought at 1st Bull Run and had been relieved

of command earlier in the war when many considered him crazy. The 5th

Division was a new division that had 8,500 green troops, mostly Ohio men

in four brigades. BG Benjamin Prentiss commanded Grant’s nal division,

the 6th. Prentiss was an Illinois lawyer with little military experience. He

had feuded with Grant in 1861 over his date of rank, and their relationship

was strained. The 6th Division was organized on 22 March 1862 and con-

tained 4,000 inexperienced troops in two brigades.

Buell brought four divisions of 18,000 men of the Army of the Ohio to

Shiloh. BG Alexander McCook, of the famous Ohio “Fighting McCooks,”

commanded the 7,500-man 2d Division. BG William “Bull” Nelson had

4,500 men in his 4th Division. The 5th Division was commanded by BG

Thomas Crittenden and had 4,000 troops. BG T.J. Wood had 2,000 men in

the 6th Division.

General Albert Sidney Johnston was the commander of the Confederate

Army of the Mississippi, and General Pierre Gustave Toutant Beauregard

was his second in command. The two enjoyed a professional relationship,

but their command system can best be described as “co-command.” When

the Confederacy abandoned its cordon defense scheme in the west and

decided to mass at Corinth, the Army of the Mississippi grew with the ad-

dition of troops from all over the South. Beauregard had 11,000 men in the

vicinity of Corinth, and Johnston brought 17,000 from Murfreesboro. MG

Braxton Bragg brought 10,000 men from the defenses of Pensacola and

Mobile. BG Daniel Ruggles brought 5,000 men from New Orleans. When

concentrated, the Army of the Mississippi had 46,000 men, the vast major-

ity of whom were untested in battle. In March, Johnston and Beauregard

organized the army into four corps.

10

11

MG Leonidas Polk commanded the I Corps. Polk was known as the

“Bishop General” because he had resigned his commission 6 months af-

ter graduating from West Point to enter the ministry, eventually rising to

Missionary Bishop of the Southwest. The I Corps had 9,100 men in two

divisions. The II Corps fell under the command of MG Braxton Bragg.

Bragg was a West Point graduate who thus far had spent the war in charge

of defending Pensacola and Mobile. His corps was the largest in the army,

14,000 men in two divisions. Interestingly, Bragg was also appointed the

army’s chief of staff in addition to being one of its corps commanders. MG

William J. Hardee commanded the III Corps. Hardee had graduated from

West Point, and soldiers on both sides were using the manual on infantry

tactics he had written for the US Army in the 1850s. The III Corps con-

sisted of 6,700 troops in three brigades; there was no divisional structure.

BG John C. Breckinridge commanded the Reserve Corps. Breckenridge

had been a very successful politician, having served in both houses of the

US Congress and as President James Buchanan’s vice president. Like the

III Corps, the Reserve Corps’ 6,700 men were in three brigades with no

divisional structure.

Weapons

Infantry

During the 1850s, in a technological revolution of major proportions,

the rie musket began to replace the relatively inaccurate smoothbore

musket in ever-increasing numbers, both in Europe and America. This

process, accelerated by the American Civil War, ensured that the ried

shoulder weapon would be the basic weapon infantrymen used in both the

Federal and Confederate armies.

The standard and most common shoulder weapon used in the American

Civil War was the Springeld .58-caliber rie musket, models 1855, 1861,

and 1863. In 1855, the US Army adopted this weapon to replace the .69-

caliber smoothbore musket and the .54-caliber rie. In appearance, the

rie musket was similar to the smoothbore musket. Both were single-shot

muzzle loaders, but the new weapon’s ried bore substantially increased

its range and accuracy. Claude Minié, a French Army ofcer, designed the

riing system the United States chose. Whereas earlier ries red a round,

nonexpanding ball, the Minié system used a hollow-based cylindro-conoi-

dal projectile slightly smaller than the bore that could be dropped easily

into the barrel. When a fulminate of mercury percussion cap ignited the

powder charge, the released propellent gases expanded the base of the bul-

let into the ried grooves, giving the projectile a ballistic spin.

10

11

The model 1855 Springeld rie musket was the rst regulation arm

to use the hollow-base .58-caliber Minié bullet. The slightly modied

model 1861 was the principal infantry weapon of the Civil War, although

two subsequent models were produced in almost equal quantities. The

model 1861 was 56 inches long overall, had a 40-inch barrel, and weighed

8.75 pounds. It could be tted with a 21-inch socket bayonet (with an 18-

inch blade, 3- inch socket) and had a rear sight graduated to 500 yards.

The maximum effective range of the Springeld rie musket was approxi-

mately 500 yards, although it could kill at 1,000 yards. The round could

penetrate 11 inches of white pine board at 200 yards and 3 inches at

1,000 yards, with penetration of 1 inch being considered the equivalent

of disabling a human being. Range and accuracy were increased by using

the new weapon, but the soldiers’ vision was still obscured by the dense

clouds of smoke its black powder propellant produced.

To load a muzzleloading rie, a soldier took a paper cartridge in hand

and tore the end of the paper with his teeth. Next he poured the powder

down the barrel and placed the bullet in the muzzle. Then, using a metal

ramrod, he pushed the bullet rmly down the barrel until seated. He then

cocked the hammer and placed the percussion cap on the cone or nipple

that when struck by the hammer ignited the gunpowder. The average rate

of re was three rounds per minute. A well-trained soldier could possibly

load and re four times per minute, but in the confusion of battle, the rate

of re was probably slower, perhaps two to three rounds per minute.

In addition to the Springelds, more than 100 types of muskets, ries,

rie muskets, and ried muskets—ranging up to .79 caliber—were used

during the American Civil War. The numerous American-made weapons

were supplemented early in the conict by a variety of imported models.

The best, most popular, and most numerous of the foreign weapons was

the British .577-caliber Eneld rie, model 1853, that was 54 inches long

(with a 39-inch barrel), weighed 8.7 pounds (9.2 with the bayonet), could

be tted with a socket bayonet with an 18-inch blade, and had a rear sight

graduated to a range of 800 yards. The Eneld design was produced in a

variety of forms, both long and short barreled, by several British manu-

facturers and at least one American company. Of all the foreign designs,

the Eneld most closely resembled the Springeld in characteristics and

capabilities. The United States purchased more than 436,000 Eneld

pattern weapons during the war. Statistics on Confederate purchases are

more difcult to ascertain, but a report dated February 1863 indicates that

70,980 long Enelds and 9,715 short Enelds had been delivered by that

time, with another 23,000 awaiting delivery.

12

13

While the quality of imported weapons varied, experts considered

the Enelds and the Austrian Lorenz rie muskets to be very good. Some

foreign governments and manufacturers took advantage of the huge initial

demand for weapons by dumping their obsolete weapons on the American

market. This practice was especially prevalent with some of the older

smoothbore muskets and converted intlocks. The greatest challenge,

however, lay in maintaining these weapons and supplying ammunition

and replacement parts for calibers ranging from .44 to .79. The quality of

the imported weapons eventually improved as the procedures, standards,

and purchasers’ astuteness improved. For the most part the European sup-

pliers provided needed weapons, and the newer foreign weapons were

highly regarded.

All told, the United States purchased about 1,165,000 European

ries and muskets during the war, nearly all within the rst two years.

Of these, 110,853 were smoothbores. The remainder were primarily the

French Minié ries (44,250), Austrian model 1854s (266,294), Prussian

ries (59,918), Austrian Jagers (29,850), and Austrian Bokers (187,533).

Estimates of total Confederate purchases ranged from 340,000 to 400,000.

In addition to the Enelds delivered to the Confederacy (mentioned be-

fore), 27,000 Austrian ries, 21,040 British muskets, and 2,020 Brunswick

ries were also purchased, with 30,000 Austrian ries awaiting shipment.

Breechloaders and repeating ries were available by 1861 and were

initially purchased in limited quantities, often by individual soldiers.

Generally, however, they were not issued to troops in large numbers be-

cause of technical problems (poor breech seals, faulty ammunition), fear

by the Ordnance Department that the troops would waste ammunition,

and the cost of production. The most famous of the breechloaders was the

single-shot Sharps, produced in both carbine and rie models. The model

1859 rie was .52 caliber, 47 inches long, weighing 8 pounds, while

the carbine was .52 caliber, 39 inches long, weighing 7 pounds. Both

weapons used a linen cartridge and a pellet primer feed mechanism. Most

Sharps carbines were issued to Federal cavalry units.

The best known of the repeaters was probably the seven-shot, .52-cali-

ber Spencer that also came in both rie and carbine models. The rie was

47 inches long and weighed 10 pounds, while the carbine was 39 inches

long and weighed 8 pounds. The rst mounted infantry unit to use

Spencer repeating ries in combat was Colonel (COL) John T. Wilder’s

“Lightning Brigade” on 24 June 1863 at Hoover’s Gap, Tennessee. The

Spencer was also the rst weapon the US Army adopted that red a metal-

lic rim-re, self-contained cartridge. Soldiers loaded rounds through an

12

13

opening in the butt of the stock that fed into the chamber through a tubular

magazine by the action of the trigger guard. The hammer still had to be

cocked manually before each shot.

Better than either the Sharps or the Spencer was the Henry rie. Never

adopted by the US Army in large quantity, soldiers privately purchased

them during the war. The Henry was a 16-shot, .44-caliber rimre car-

tridge repeater. It was 43 inches long and weighed 9 pounds. The

tubular magazine located directly beneath the barrel had a 15-round capac-

ity with an additional round in the chamber. Of the approximate 13,500

Henrys produced, probably 10,000 saw limited service. The government

purchased only 1,731.

The Colt repeating rie (or revolving carbine), model 1855, also was

available to Civil War soldiers in limited numbers. The weapon was pro-

duced in several lengths and calibers. The lengths varied from 32 to 42

inches, while the calibers were .36, .44, and .56. The .36 and .44 calibers

were made to chamber six shots, while the .56-caliber had ve chambers.

The Colt Firearms Company was also the primary supplier of revolvers.

The .44-caliber Army revolver and the .36-caliber Navy revolver were the

most popular (more than 146,000 purchased) because they were simple,

sturdy, and reliable.

Cavalry

Initially armed with sabers and pistols (and in one case, lances),

Federal cavalry troops quickly added the breechloading carbine to their in-

ventory of weapons. However, one Federal regiment, the 6th Pennsylvania

Cavalry, carried lances until 1863. Troopers preferred the easier-handling

carbines to ries and the breechloaders to awkward muzzleloaders. Of the

single-shot breechloading carbines that saw extensive use during the Civil

War, the Hall .52-caliber accounted for approximately 20,000 in 1861. The

Hall was quickly replaced by a variety of carbines, including the Merrill

.54 caliber (14,495), Maynard .52 caliber (20,002), Gallager .53 caliber

(22,728), Smith .52 caliber (30,062), Burnside .56 caliber (55,567), and

Sharps .54 caliber (80,512).

The next step in the evolutionary process was the repeating carbine.

The favorite by 1865 was the Spencer .52-caliber, seven-shot repeater

(94,194). Because of the South’s limited industrial capacity, Confederate

cavalrymen had a more difcult time arming themselves. Nevertheless,

they too embraced the repower revolution, choosing shotguns, muzzle-

loading carbines, and numerous revolvers as their primary weapons. In ad-

dition, Confederate cavalrymen made extensive use of battleeld salvage

14

15

by recovering Federal weapons. However, the South’s difculties in pro-

ducing the metallic-rimmed cartridges many of these recovered weapons

required limited their usefulness.

Field Artillery

In 1841 the US Army selected bronze as the standard material for

eldpieces and at the same time adopted a new system of eld artillery.

The 1841 eld artillery system consisted entirely of smoothbore muzzle-

loaders: 6- and 12-pound guns; 12-, 24-, and 32-pound howitzers; and

12-pound mountain howitzers. A pre-Civil War battery usually consisted

of six eldpieces—four guns and two howitzers. A 6-pounder battery con-

tained four 6-pound guns and two 12-pound howitzers, while a 12-pound-

er battery had four 12-pound guns and two 24-pound howitzers. The guns

red solid shot, shell, spherical case, grapeshot, and canister rounds, while

howitzers red shell, spherical case, grapeshot, and canister rounds.

The 6-pound gun (effective range of 1,523 yards) was the primary

eldpiece used from the Mexican War until the Civil War. By 1861, how-

ever, the 1841 system based on the 6-pounder was obsolete. In 1857, a

new and more versatile eldpiece, the 12-pound gun-howitzer (Napoleon),

model 1857, appeared on the scene. Designed as a multipurpose piece to

replace existing guns and howitzers, the Napoleon red canisters and

shells like the 12-pound howitzer and solid shot at ranges comparable to

the 12-pound gun. The Napoleon was a bronze, muzzleloading smooth-

bore with an effective range of 1,680 yards using solid shot (see table 3

for a comparison of artillery data). Served by a nine-man crew, the piece

could re at a sustained rate of two aimed shots per minute. With less than

50 Napoleons initially available in 1861, obsolete 6-pounders remained

in the inventories of both armies for some time, especially in the western

theater.

Another new development in eld artillery was the introduction of ri-

ing. Although ried guns provided greater range and accuracy, they were

somewhat less reliable and slower to load than smoothbores. (Ried am-

munition was semixed, so the charge and the projectile had to be loaded

separately.) Moreover, the canister load of the rie did not perform as well

as the smoothbore. Initially, some smoothbores were ried on the James

pattern, but they soon proved unsatisfactory because the bronze riing

eroded too quickly. Therefore, most ried artillery was wrought iron or

cast iron with a wrought iron reinforcing band encircling the breach area.

The most common ried guns were the 10-pound Parrott and the

Rodman, or 3-inch ordnance rie. The Parrott rie was a cast-iron piece,

14

15

easily identied by the wrought-iron band reinforcing the breech. The 10-

pound Parrott was made in two models: the model 1861 had a 2.9-inch

ried bore with three lands and grooves and a slight muzzle swell, while

the model 1863 had a 3-inch bore and no muzzle swell. The Rodman, or

ordnance rie, was a long-tubed, wrought-iron piece that had a 3-inch bore

with seven lands and grooves. Ordnance ries were sturdier than the 10-

pound Parrott and displayed superior accuracy and reliability.

By 1860 the ammunition for eld artillery consisted of four general

types for both smoothbores and ries: solid shot, shell, case, and canister.

Solid shot for smoothbores was a round cast-iron projectile; for ried guns

it was an elongated projectile known as a bolt. Solid shot, with its smash-

ing or battering effect, was used in a counterbattery role or against build-

ings and massed troop formations. The rie’s conical-shaped bolt lacked

the effectiveness of the smoothbore’s cannonball because it tended to bury

itself upon impact instead of bounding along the ground like round shot.

Shell, also known as common or explosive shell, whether spherical or

conical, was a hollow projectile lled with an explosive charge of black

powder detonated by a fuse. Shell was designed to break into jagged

pieces, producing an antipersonnel effect, but the low-order detonation

seldom produced more than three to ve fragments. In addition to its

casualty-producing effects, shell had a psychological impact when it

exploded over troops’ heads. It was also used against eld fortications

and in a counterbattery role. Case or case shot for both smoothbore and

ried guns was a hollow projectile with thinner walls than shell. The

projectile was lled with round lead or iron balls set in a matrix of sulfur

that surrounded a small bursting charge. Case was primarily used in an

antipersonnel role. Henry Shrapnel, a British artillery ofcer, invented this

type of round, hence the term “shrapnel.”

Finally there was canister, probably the most effective round and the

round of choice at close range (400 yards or less) against massed troops.

Canister was essentially a tin can lled with iron balls packed in sawdust

with no internal bursting charge. When red, the can disintegrated, and

the balls followed their own paths to the target. The canister round for

the 12-pound Napoleon consisted of 27 1 -inch iron balls packed inside

an elongated tin cylinder. At extremely close ranges of 200 yards or less,

artillerymen often loaded double charges of canister.

Heavy Artillery—Siege and Seacoast

The 1841 artillery system listed eight types of siege artillery and an-

other six types as seacoast artillery. The 1861 Ordnance Manual included

16

17

11 different kinds of siege ordnance. The principal siege weapons in 1861

were the 4.5-inch rie; 18- and 24-pound guns; a 24-pound howitzer and

two types of 8-inch howitzer; and several types of 8- and 10-inch mortars.

The normal rate of re for siege guns and mortars was about 12 rounds

per hour, but with a well-drilled crew, this could probably be increased to

about 20 rounds per hour. The rate of re for siege howitzers was some-

what lower, being about eight shots per hour.

The carriages for siege guns and howitzers were longer and heavier

than eld artillery carriages but were similar in construction. The model

1839 24-pounder was the heaviest piece that could be moved over the

roads of the day. Alternate means of transport, such as railroad or water-

craft, were required to move larger pieces any great distance.

The rounds that siege artillery red were generally the same as those

eld artillery red except that siege artillery continued to use grapeshot

after it was discontinued in the eld artillery (1841). A “stand of grape”

consisted of nine iron balls ranging from 2 to about 3 inches in diameter,

depending on gun caliber.

The largest and heaviest artillery pieces in the Civil War era belonged

to the seacoast artillery. These large weapons were normally mounted in

xed positions. The 1861 system included ve types of columbiads rang-

ing from 8- to 15-inch; 32- and 42-pound guns; 8- and 10-inch howitzers;

and mortars of 10 and 13 inches.

Wartime additions to the Federal seacoast artillery inventory included

Parrott ries ranging from 6.4-inch to 10-inch (300-pounder). New colum-

biads, developed by ordnance Lieutenant Thomas J. Rodman, included

8-inch, 10-inch, and 15-inch models. The Confederates produced some

new seacoast artillery of their own—Brooke ries in 6.4- and 7-inch ver-

sions. They also imported weapons from England, including 7- and 8-inch

Armstrong ries, 6.3- to 12.5-inch Blakely ries, and 5-inch Whitworth

ries.

Seacoast artillery red the same projectiles as siege artillery, but with

one addition—hot shot. As its name implies, hot shot was solid shot heated

in special ovens until red-hot, then carefully loaded and red as an incen-

diary round.

Weapons at Shiloh

Neither side fought the Battle of Shiloh with its soldiers armed with

the most modern weapons available. In one of the few times during the

American Civil War, the Union did not enjoy an advantage of superior

16

17

Table 3. Common Types of Artillery Available at the Battle of Shiloh

infantry weapons. Most of the Union soldiers were armed with either the

US model 1841 ried musket (.69 caliber) or the US model 1842 smooth-

bore musket (.69 caliber). Some entire regiments were outtted with mod-

ern weapons like the US model 1855 Springeld rie (.58 caliber) or the

imported British Eneld rie (.577 caliber).

The Confederates were armed with an assortment of weapons. Some

regiments had a combination of many different weapons. Most Con-

federate soldiers were armed with obsolete weapons, smoothbores and

intlocks converted to percussion cap. Some units were even armed with

hunting ries. The Army of the Mississippi had approximately 4,000 En-

eld ries that had come through the blockade and were shipped west in

November 1861. Following the assault on the Hornet’s Nest, the Confed-

erates increased the total number of Enelds in the army. Two regiments

immediately swapped their old weapons for Eneld ries that Union

troops surrendered.

The Union and Confederate forces had artillery parity at Shiloh; Grant

had 119 cannon and Johnston had 117. Union forces organized their artil-

lery differently in each division. Some brigades had an artillery battery,

but in four of the six divisions in the Army of the Tennessee, the artillery

was informally consolidated at division level. Each Confederate brigade at

Shiloh had at least one artillery battery assigned; MG Patrick R. Cleburne’s

brigade had an entire battalion of artillery. While artillery weapons had

been modernized in the east, the new pieces had not reached the western

Field Artillery

Tube Range

Bore Length Tube Carriage (yards)/

Diameter Overall Weight Weight degrees

Type Model (inches) (inches) (pounds) (pounds) elevation

Smoothbore

6-pound Gun 3.67 65.6 884 900 1,523/5°

12-pound Gun-

“Napoleon” Howitzer 4.62 72.15 1,227 1,128 1,680/5°

12-pound Howitzer 4.62 58.6 788 900 1,072/5°

24-pound Howitzer 5.82 71.2 1,318 1,128 1,322/5°

Rie

10-pound Parrott

3.0 78 890 900 2,970/10°

3-inch Ordnance 3.0 73.3 820 900 2,788/10°

20-pound Parrott 3.67 89.5 1,750 4,400/15°

18

19

armies at Shiloh. Half of the Union artillery weapons were “leftovers”

from the 1841 system, while more than 80 percent of the Confederate can-

non were out of date. There was no formal artillery command and control

function for either side. The infantry commanders controlled their own ar-

tillery or left its employment up to the battery ofcers. This made massing

artillery res difcult. Massed res of more than 25 cannon only occurred

three times during the battle.

Two of the massed artillery rings proved decisive: Ruggles’ bom-

bardment at the Hornet’s Nest and Grant’s last line at Pittsburg Landing.

The artillery ofcers for each side were inexperienced and attempted to

use antiquated Napoleonic tactics. On occasion, artillery went into battle

within 400 yards of the enemy with the intent of ring canister. As they

unlimbered their pieces, they were cut to pieces by the shoulder weapons

the infantryman carried. Artillerymen suffered heavy casualties at Shiloh.

The Union artillery lost 32 killed, 245 wounded, and four missing. The

Confederates had 40 artillerymen killed, 169 wounded, and ve missing.

The naval gunre support from the USS Tyler and the USS Lexington was

effective and more than likely inuenced Beauregard’s decision to stop the

battle on the rst day. The re from their 32-pound and 8-inch guns caused

some casualties, but the psychological effect was substantially greater.

Tactics

Tactical Doctrine in 1861

The Napoleonic Wars and the Mexican War were the major inu-

ences on American tactical thinking at the beginning of the Civil War. The

campaigns of Napoleon Bonaparte and the Duke of Wellington provided

ample lessons in battle strategy, weapons employment, and logistics,

while American tactical doctrine reected the lessons learned in Mexico

(1846-48). However, these tactical lessons were misleading because in

Mexico relatively small armies fought only seven pitched battles. Because

these battles were so small, almost all the tactical lessons learned during

the war focused at the regiment, battery, and squadron levels. Future Civil

War leaders had learned very little about brigade, division, and corps ma-

neuver in Mexico, yet these units were the basic ghting elements of both

armies in 1861-65.

The US Army’s experience in Mexico validated Napoleonic prin-

ciples—particularly that of the offensive. In Mexico, tactics did not differ

greatly from those of the early 19th century. Infantry marched in columns

and deployed into lines to ght. Once deployed, an infantry regiment might

send one or two companies forward as skirmishers, as security against sur-

18

19

prise, or to soften the enemy’s line. After identifying the enemy’s position,

a regiment advanced in closely ordered lines to within 100 yards. There it

delivered a devastating volley, followed by a charge with bayonets. Both

sides used this basic tactic in the rst battles of the Civil War.

In Mexico, American armies employed artillery and cavalry in both

offensive and defensive battle situations. In the offense, artillery moved as

near to the enemy lines as possible—normally just outside musket range

of about 200 yards—to blow gaps in the enemy’s line that the infantry

might exploit with a determined charge. In the defense, artillery blasted

advancing enemy lines with canister and withdrew if the enemy attack got

within musket range. Cavalry guarded the Army’s anks and rear but held

itself ready to charge if enemy infantry became disorganized or began to

withdraw.

These tactics worked perfectly well with the weapons technology of

the Napoleonic and Mexican wars. The infantry musket was accurate up

to 100 yards but ineffective against even massed targets beyond that range.

Ries were specialized weapons with excellent accuracy and range but

slow to load and therefore not usually issued to line troops. Smoothbore

cannon had a range up to 1 mile with solid shot but were most effective

against infantry when ring canister at ranges under 400 yards. Artillerists

worked their guns without much fear of the infantry muskets’ limited

range. Cavalry continued to use sabers and lances as shock weapons.

American troops took the tactical offensive in most Mexican War bat-

tles with great success, and they suffered fairly light losses. Unfortunately,

similar tactics proved to be obsolete in the Civil War because of a major

technological innovation elded in the 1850s—the cylindro-conoidal rie

musket. This new weapon greatly increased the infantry’s range and accu-

racy and loaded as fast as a musket. The US Army adopted a version of the

rie musket in 1855, and by the beginning of the Civil War, rie muskets

were available in moderate numbers. It was the weapon of choice in both

the Union and Confederate Armies during the war, and by 1862, large

numbers of troops on both sides had good-quality rie muskets.

Ofcial tactical doctrine before the beginning of the Civil War did

not clearly recognize the potential of the new rie musket. Before 1855

the most inuential tactical guide was MG Wineld Scott’s three-vol-

ume work, Infantry Tactics (1835), based on French tactical models of

the Napoleonic Wars. It stressed close-order, linear formations in two or

three ranks advancing at “quick time” of 110 steps (86 yards) per minute.

In 1855, to accompany the introduction of the new rie musket, Major

20

21

William J. Hardee published a two-volume tactical manual, Rie and

Light Infantry Tactics. Hardee’s work contained few signicant revisions

of Scott’s manual. His major innovation was to increase the speed of the

advance to a “double-quick time” of 165 steps (151 yards) per minute. If,

as suggested, Hardee introduced his manual as a response to the rie mus-

ket, then he failed to appreciate the weapon’s impact on combined arms

tactics and the essential shift the rie musket made in favor of the defense.

Hardee’s Tactics was the standard infantry manual both sides used at the

outbreak of war in 1861.

If Scott’s and Hardee’s works lagged behind technological innova-

tions, at least the infantry had manuals to establish a doctrinal basis for

training. Cavalry and artillery fell even farther behind in recognizing

the potential tactical shift in favor of rie-armed infantry. The cavalry’s

manual, published in 1841, was based on French sources that focused

on close-order offensive tactics. It favored the traditional cavalry attack

in two ranks of horsemen armed with sabers or lances. The manual took

no notice of the rie musket’s potential, nor did it give much attention to

dismounted operations. Similarly, the artillery had a basic drill book delin-

eating individual crew actions, but it had no tactical manual. Like cavalry-

men, artillerymen showed no concern for the potential tactical changes the

rie musket implied.

Regular Army infantry, cavalry, and artillery troops practiced and

became procient in the tactics that brought success in Mexico. As the

rst volunteers drilled and readied themselves for the battles of 1861, of-

cers and noncommissioned ofcers taught the lessons learned from the

Napoleonic Wars that were validated in Mexico. Thus, the two armies

entered the Civil War with a good understanding of the tactics that had

worked in the Mexican War but with little understanding of how the rie

musket might upset their carefully practiced lessons.

Early War Tactics

In the battles of 1861 and 1862, both sides employed the tactics

proven in Mexico and found that the tactical offensive could still be suc-

cessful—but only at a great cost in casualties. Men wielding ried weap-

ons in the defense generally ripped frontal assaults to shreds, and if the

attackers paused to exchange re, the slaughter was even greater. Ries

also increased the relative numbers of defenders since anking units now

engaged assaulting troops with a murderous enlading re. Defenders

usually crippled the rst assault line before a second line of attackers

could come forward in support. This caused successive attacking lines to

20

21

intermingle with survivors to their front, thereby destroying formations,

command, and control. Although both sides favored the bayonet through-

out the war, they quickly discovered that rie musket re made successful

bayonet attacks almost impossible.

Just as infantry troops found the bayonet charge to be of little value

against rie muskets, cavalry and artillery troops made troubling discov-

eries of their own. Cavalry troops soon learned that the old-style saber

charge did not work against infantry troops armed with rie muskets.

Cavalry troops, however, retained their traditional intelligence-gathering

and screening roles whenever commanders chose to make the horsemen

the “eyes and ears” of the Army. Artillery troops found that they could not

maneuver freely to canister range as they had in Mexico because the rie

musket was accurate beyond that distance. Worse yet, at ranges where

gunners were safe from rie re, artillery shot, shell, and case were far less

effective than close-range canister. Ironically, ried cannon did not give

the equivalent boost to artillery effectiveness that the rie musket gave to

the infantry. The cannons’ increased range proved to be no real advantage

in the broken and wooded terrain over which so many Civil War battles

were fought.

There are several possible reasons why Civil War commanders con-

tinued to employ the tactical offensive long after it was clear that the

defensive was superior. Most commanders believed the offensive was the

decisive form of battle. This lesson came straight from the Napoleonic

Wars and the Mexican-American War. Commanders who chose the tacti-

cal offensive usually retained the initiative over defenders. Similarly, the

tactical defensive depended heavily on the enemy attacking at a point that

was convenient to the defender and continuing to attack until badly it was

defeated. Although this situation occurred often in the Civil War, a prudent

commander could hardly count on it for victory. Consequently, few com-

manders chose to exploit the defensive form of battle if they had the option

to attack.

The offensive may have been the decisive form of battle, but it was

very hard to coordinate and even harder to control. The better generals

often tried to attack the enemy’s anks and rear but seldom achieved

success because of the difculty involved. Not only did the commander

have to identify the enemy’s ank or rear correctly, he also had to move

his force into position to attack and do so in conjunction with attacks that

other friendly units made. Command and control of the type required to

conduct these attacks was quite beyond most Civil War commanders’ abil-

ity. Therefore, Civil War armies repeatedly attacked each other frontally,

22

23

resulting in high casualties, because that was the easiest way to conduct

offensive operations. When attacking frontally, a commander had to

choose between attacking on a broad front or a narrow front. Attacking on

a broad front rarely succeeded except against weak and scattered defend-

ers. Attacking on a narrow front promised greater success but required im-

mediate reinforcement and continued attack to achieve decisive results. As

the war dragged on, attacking on narrow fronts against specic objectives

became a standard tactic that fed ever-growing casualty lists.

Later War Tactics

Poor training may have contributed to high casualty rates early in the

war, but casualties remained high and even increased long after the armies

became experienced. Continued high casualty rates resulted because

tactical developments failed to adapt to new weapons technology. Few

commanders understood how the rie musket strengthened the tactical de-

fensive. However, some commanders made offensive innovations that met

with varying success. When an increase in the speed of the advance did

not overcome defending repower (as Hardee suggested it would), some

units tried advancing in more open order. But this sort of formation lacked

the appropriate mass to assault and carry prepared positions and created

command and control problems beyond the Civil War leaders’ ability to

resolve. Late in the war, when the difculty of attacking eld fortica-

tions under heavy re became apparent, other tactical expedients were

employed. Attacking solidly entrenched defenders often required whole

brigades and divisions moving in dense masses to rapidly cover interven-

ing ground, seize the objective, and prepare for the inevitable counterat-

tack. Seldom successful against alert and prepared defenses, these attacks

were generally accompanied by tremendous casualties and foreshadowed

the massed infantry assaults of World War I.

Sometimes large formations attempted mass charges over short

distances without halting to re. This tactic enjoyed limited success at

Spotsylvania Court House in May 1864. At Spotsylvania, a Union division

attacked and captured an exposed portion of the Confederate line. The at-

tack succeeded because the Union troops crossed the intervening ground

very quickly without artillery preparation and without stopping to re their

ries. Once inside the Confederate defenses, the Union troops attempted

to exploit their success by continuing their advance, but loss of command

and control rendered them little better than a mob. Counterattacking

Confederate units in conventional formations eventually forced the

Federals to relinquish much of the ground they had gained.

22

23

As the war dragged on, tactical maneuver focused more on larger for-

mations—brigade, division, and corps. In most of the major battles fought

after 1861, brigades were employed as the primary maneuver formations,

but brigade maneuver was at the upper limit of command and control for

most Civil War commanders. Brigades might have been able to retain

coherent formations if the terrain had been suitably open, but most often,

brigade attacks degenerated into a series of poorly coordinated regimental

lunges through broken and wooded terrain. Thus, brigade commanders

were often on the main battle line trying to inuence regimental ghts.

Typically, defending brigades stood in the line of battle and blazed away

at attackers as rapidly as possible. Volley re usually did not continue be-

yond the rst round. Most of the time soldiers red as soon as they were

ready, and it was common for two soldiers to work together, one loading

while the other red. Brigades were generally invulnerable to attacks on

their front and anks if units to the left and right held their ground or if

reinforcements came up to defeat the threat.

Two or more brigades constituted a division. When a division at-

tacked, its brigades often advanced in sequence, from left to right or vice

versa—depending on terrain, suspected enemy location, and number of

brigades available to attack. At times divisions attacked with two or more

brigades leading, followed by one or more brigades ready to reinforce the

lead brigades or maneuver to the anks. Two or more divisions consti-

tuted a corps that might conduct an attack as part of a larger plan the army

commander controlled. More often, groups of divisions attacked under

the control of a corps-level commander. Division and corps commanders

generally took a position to the rear of the main line to control the ow of

reinforcements into the battle, but they often rode forward into the battle

lines to inuence the action personally.